We have grown up in a world where birth control is readily available. Now that I am in my 40’s, my tubes are tied so you might think I wouldn’t consider it a high priority. But birth control should be a knowledge priority for every prepper. While I personally no longer need to remember how to practice natural family planning, I am the mother of children who will likely marry and have their own children. It is our job as preppers to be teachers and impart as much knowledge and as many skills as possible to the next generations in a post-SHTF world, birth control knowledge included.

We have grown up in a world where birth control is readily available. Now that I am in my 40’s, my tubes are tied so you might think I wouldn’t consider it a high priority. But birth control should be a knowledge priority for every prepper. While I personally no longer need to remember how to practice natural family planning, I am the mother of children who will likely marry and have their own children. It is our job as preppers to be teachers and impart as much knowledge and as many skills as possible to the next generations in a post-SHTF world, birth control knowledge included.

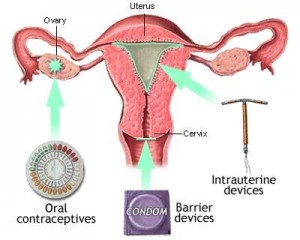

For those of you who currently use birth control but are done having children, I encourage you to look at a surgical procedure NOW to prevent unexpected conception. This is the same prepper approach of making sure we are all up to date on our medical and dental needs in case the SHTF (don’t put off the elective stuff!). For men, a vasectomy is a simple outpatient procedure with low risk of complications. For women, the tubal ligation is more involved and carries a higher risk of complications, but it is still considered a safe outpatient procedure. And both are considered routine elective surgeries covered by almost every health insurance plan. Should you choose not to go with the sterilization route, you can look at non-medication birth control like diaphragms/cervical caps. Although these will not last forever, they may be a more practical option than storing a case of condoms. One thing I would suggest to anyone who uses an “internal” form of birth control (such as an IUD or implant of meds), consider the potential risk of not being able to have them removed post-SHTF.

For knowledge and teaching purposes, we should all familiarize ourselves with the concept of natural family planning. And by this I do NOT mean the old school rhythm method or anything like that. I know we have all had the classes in school about reproduction, but how many of us know the intricate details well enough to teach them? I feel that the best resources for learning to avoid pregnancies are the same ones that you study for trying to get pregnant: books about infertility. There are many more resources for infertility than there are for natural family planning. Infertility books focus, in minute detail, on the signs and symptoms of the fertility cycle. Basically, by studying how to get pregnant you can also learn how to avoid pregnancy–you are studying with a “WHAT NOT TO DO” approach; essentially learning when to avoid sexual activity. This is not 100% fail safe because women do not all have the same biology. But it is the best possibility we have of avoiding pregnancy without modern medicine.

For knowledge and teaching purposes, we should all familiarize ourselves with the concept of natural family planning. And by this I do NOT mean the old school rhythm method or anything like that. I know we have all had the classes in school about reproduction, but how many of us know the intricate details well enough to teach them? I feel that the best resources for learning to avoid pregnancies are the same ones that you study for trying to get pregnant: books about infertility. There are many more resources for infertility than there are for natural family planning. Infertility books focus, in minute detail, on the signs and symptoms of the fertility cycle. Basically, by studying how to get pregnant you can also learn how to avoid pregnancy–you are studying with a “WHAT NOT TO DO” approach; essentially learning when to avoid sexual activity. This is not 100% fail safe because women do not all have the same biology. But it is the best possibility we have of avoiding pregnancy without modern medicine.

There may be natural birth control products that you want to study and read up about. There are even a number of semi-useful ideas that evolved into modern-day birth control (bolstered by medications and chemicals). For instance, for centuries women made their own contraceptive sponges that they soaked in some liquid with sperm killing properties. This is an early predecessor to the Today brand contraceptive sponges. There are useful ideas out there, but you will need to weed out the old wives tales from the practical knowledge.

Why do I feel birth control is so important? Why do I think we all need to intimately understand natural family planning? Quite simply, pregnancy without medical care (i.e. a post-SHTF society) will mean an increased death-rate for women and newborns. My first child was over ten pounds and I had to have a complicated and risky C-Section (excessively large babies and twins run in our family.) In a post-SHTF world, that is a risk we would all want to avoid for our children. Remember that this topic is important and make sure you’re prepared with the knowledge to get it right when it is your turn to teach.

Why do I feel birth control is so important? Why do I think we all need to intimately understand natural family planning? Quite simply, pregnancy without medical care (i.e. a post-SHTF society) will mean an increased death-rate for women and newborns. My first child was over ten pounds and I had to have a complicated and risky C-Section (excessively large babies and twins run in our family.) In a post-SHTF world, that is a risk we would all want to avoid for our children. Remember that this topic is important and make sure you’re prepared with the knowledge to get it right when it is your turn to teach.

(Friday: What We Did This Week To Prep)